Figurative Artist Handbook: Blocking in with Anatomy, Light, and Shadow

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Drawing New York is thrilled to partner with artist Rob Zeller, author of The Figurative Artist’s Handbook to offer our members a ‘serialized digest’ of his extremely popular and beautiful book. Each week we will bring you new topics and techniques relating to figure drawing so check back often.[/vc_column_text][thb_gap height=”22″][vc_text_separator title=”Blocking In With Anatomy, Light, and Shadow” color=”sandy_brown”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]Blocking in refers to a drawing process that moves from the general to the specific, whereby the largest shapes are first mapped out, and then broken down into smaller, more manageable units. Blocking in is a strictly perceptual endeavor where the artist sees, and thinks, only of shapes.

You have to understand how the figure is put together in an architectural sense to create a believable representation of a human. The strictly perceptual block in is fine for still lifes, and even (to some degree) landscapes, but when used with the figure it proves insufficient. You must know anatomy and then be able to see and understand the anatomy of the model you are drawing.[/vc_column_text][thb_gap height=”22″][vc_btn title=”Click Here to Order The Figurative Artist’s Handbook” style=”classic” color=”sandy-brown” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Famzn.to%2F2LbVjPN||target:%20_blank|”][vc_column_text]THE BASIC ANATOMICAL FORMS

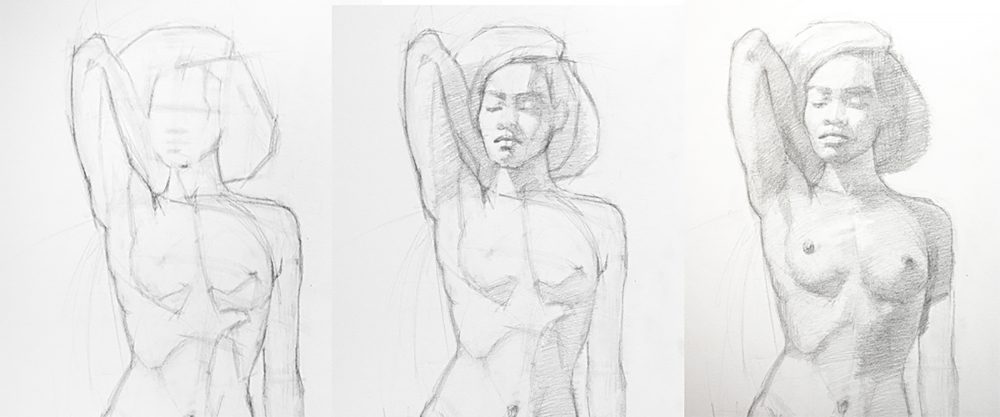

Notice in the preliminary block in that I mapped out the joints, with light marks that could be moved if needed. I put in the three major masses: head, rib cage, and pelvis. They are all accounted for. The gesture lines I was searching for in the very beginning dictated their positioning.

Legs and Pelvis

Legs and Pelvis

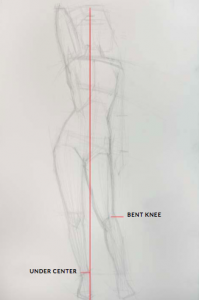

In a standing pose, you should pay special attention to the structure of the legs and pelvis. As such, you will need to memorize the bones and muscles of the leg. First, find the leg that falls “under center.” That’s the stand leg. The other (the balance leg) usually has a bend the knee. Then map out the major boxes and joints. In a normal standing pose with a bent leg, you can drop a straight line (a plumb line) from the head down to the inside ankle of the stand leg, as shown opposite.

Regarding the feet, draw a line, in perspective, on the ground plane that follows the footprint of each foot. Then draw the outline of a foot on top of that line. The most important thing to capture in terms of the feet, in this initial stage, is in what directions they point.

At this early stage of the block in, focus on the legs and pelvis till they appear architecturally solid enough to hold the model upright. This simply means determining the correct proportions, tilts, and central axis for each of them. Again, at this point you are not looking for details in any particular muscle yet, but more for their overall shapes.

Torso and Head

Next, consider the torso, which is a combination of the rib cage and the head. Think of this sequence as a progression in geometry: from squares to circles, from lines to curves. The rib cage can be seen as essentially barrel- or egg-shaped, existing within a vertical rectangle.

At this early stage, the head should be blocked in as minimally and economically as possible. It is much more important to concentrate on placing the head in space correctly.[/vc_column_text][thb_gap height=”22″][vc_column_text]THE SEPARATION OF LIGHT AND SHADOW

In classical drawing and painting, it’s important to let light unify your work. Each of the major forms should have a dividing line between light and shadow. This line is known as a terminator. Light does not go past the form at that point.

Think of it as “outlining” the shadow, in the same way you would outline the shape of an arm or a face. Shadows make shapes that are just as important.

A FOCUS ON THE FACE

I use spatial coordinates to put the head in its proper position on the torso. In essence, I am mapping points on the figure’s skeleton.

At this point in the process, I’m looking for symmetry and asymmetry. The human figure has both aspects, and these vary from individual to individual.

After mapping out the skeletal

points, I try to chisel out the largest

planes and describe their forms by

how much light they catch. I also try

to observe the way the forms are interconnected among their planes. The ability to switch to an observational mode while simultaneously working conceptually takes time and experience.[/vc_column_text][thb_gap height=”22″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”home_1″][thb_gap height=”22″][vc_column_text]Top Image: Elizabeth Zanzinger, Fallon III, 2015, graphite on Mylar, 18 x 14 inches (45.7 x 35.6 cm) The power and rhythm of the lines the model created resonated with the artist. To Zanzinger, her body echoed the remnants of the animal skull she’s holding.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][ultimate_author_box user_id=”139″ template=’uab-template-12′][/vc_column_text][thb_gap height=”10″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Responses